Fact sheet 06-2016

A Value-based, Digitally Supported, Person-centred Care System - National and International Trends

Downloadable PDF

Fact-sheet-2016-06-A-value-based-care-system.pdf

Faktaark-2016-06-Et-verdibasert-personsentrert-omsorgssystem.pdf

Patients with multiple long term conditions (multi-LTC) typically face multiple care processes, care providers, organizations and specialties over longer periods.[1] Current care systems both internationally and in Norway are profession centric, re-active and characterized by a disintegration of both responsibility and information flow.[2, 3] This is especially challenging to the quality of care for multi-LTC patients.[1, 3-5] Multi-LTC patients dominate the top 10%-spenders who account for 2/3 of all specialist healthcare resources.[6, 7] Suboptimal quality of care is not only a source of human suffering; it also drives health care costs for this patient group.[5, 8]

Rising costs, increased proportion of patients with multi-LTCs and longevity are threatening the sustainability of our health care systems.9 Current ICT infrastructures tend to mirror and solidify organizational fragmentation. Unfortunately, national and international publications show the same system failures across western care for this patient group.[1,2]

Current literature points to the Chronic Care Model (CCM) as the best-documented and most widely studied model of care for patients with multi-LTCs. It has both a systems, a clinical, and a patient perspective,[10] and a growing evidence base for effects on both care-processes, health outcomes and cost-effectiveness.[11-13] The CCM builds on two pillars: “The informed active patient” and “The pro-active prepared health care team” engaging in “productive interactions” for “health and functional outcomes”.

Although the CCM is both intuitive and well accepted, it does not specify how to operationalize these ideas. International recommendations call for a transformation from profession to person centric, from episodic to process oriented, from re-active to pro-active and from single-disease to coordinated team-based care.[14] The Norwegian context is in no way unique, as care systems struggle to reform care all over the globe.[14, 15] ICT is a key strategic component of CCM-success. In an ambitious white paper, “One citizen, one EHR”, the Norwegian health authorities recognize ICT as a strategic tool not only for improved workflow and quality of care, but also vital to health policy objectives of user involvement, self-care and self-determination.

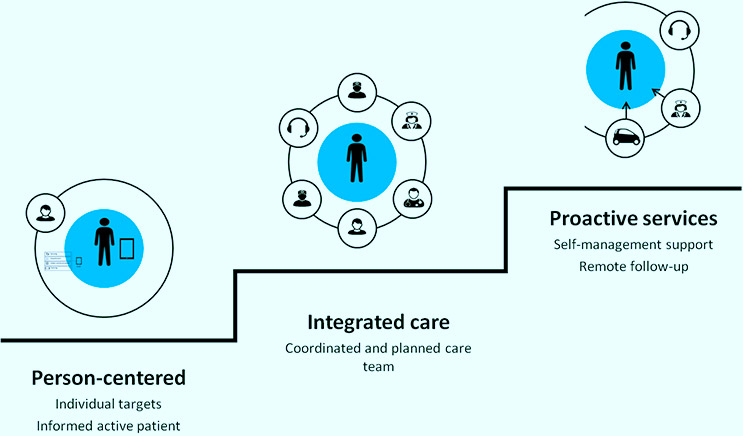

In pursuit of more tangible strategies, researchers recommend transformation of care, leveraged by digital tools, that has three main characteristics: Person-centred, Integrated and Pro-active care.[15, 16]

Step 1: The Person-centred care: the PCC component is the basic foundation for a partnership between professionals and persons. A person-centred service elicits, responds to and is loyal to the patients answer to the question: “What is important to you?”. Based on this, individual realistic goals for care can be formulated. Such goals are the starting points for coordinated plans, and patient driven evaluation and adjustment of care.

Step 2: Integrated care team: When goals are clear, it is easier to prioritize the types of competency that is needed to design and implement a patient pathway aligned with the goals. The professional team all work together with complementary skills towards a common goal. Note – without a common goal from step 1, the team coordination falls apart.

Step 3: Proactive and planned care: Pro-active care starts by patient self-management support, which allows the person who has the most to gain from early low-level intervention to do his/her job effectively. In addition, the care plan should include both elective and emergency care components of evidence based guidelines, when these are available, and they are aligned with the individual patient goals. Finally, for a small proportion of patients, remote follow-up with sensors and/ or self-report may help identify situations marked by increased risk of preventable crises. Note – without an identified team from step 2, the pro-active integrated care plan cannot be assembled.

References

- Tinetti ME, Fried T, Boyd C. DEsigning health care for the most common chronic condition—multimorbidity. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association 2012;307(23):2493-94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5265

- Care ITISfQiH, ed. The Perspectives Of Patients With Complex, Long-Term Pathways: A Mixed Method Analysis In Light Of Recommended Practice. # 1937. 32nd International Conference: Building Quality and Safety into the Healthcare System, 4th - 7th October; 2015; National Convention Center, Doha, Qatar.

- Bayliss EA, Edwards AE, Steiner JF, et al. Processes of care desired by elderly patients with multimorbidities. Family Practice 2008;25(4):287-93. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn040

- Relman A. On Breaking One’s Neck. The New York Review of Books 2014 Feb 6, 2014.

- Wallace E, Salisbury C, Guthrie B, et al. Managing patients with multimorbidity in primary care. BMJ 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h176

- Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2007;22 Suppl 3:391-5.

- Helsedirektoratet. Prioriteringer I helsesektoren – Verdigrunnlag, status og utfordringer, 2012.

- Salisbury C, Johnson L, Purdy S, et al. Epidemiology and impact of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. British Journal of General Practice 2011;61(582):e12-e21.

- Heiberg I. High utilisators of somatic specialist health care in Northern Norway. [Storforbrukere av somatisk spesialisthelsetjeneste i Helse Nord]: SKDE; 2015 [Available from: http://www.helse-nord.no/getfi... accessed 2015-12-06.

- Scott IA, Shohag H, Ahmed M. Quality of care factors associated with unplanned readmissions of older medical patients: a case–control study. Intern Med J 2014;44(2):161-70. doi: 10.1111/imj.12334

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The Triple Aim: Care, Health, And Cost. Health Affairs 2008;27(3):759-69. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, VonKorff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Quarterly 1996;74(4):511-&.

- Scott IA. Chronic disease management: a primer for physicians. Intern Med J 2008;38(6):427-37.

- de Bruin SR, Versnel N, Lemmens LC, et al. Comprehensive care programs for patients with multiple chronic conditions: A systematic literature review. Health Policy 2012;107(2-3):108-45. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpo1.2012.06.006

- Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The Group Health Medical Home At Year Two: Cost Savings, Higher Patient Satisfaction, And Less Burnout For Providers. Health Affairs 2010;29(5):835.

- Epping-Jordan JE, Pruitt SD, Bengoa R, et al. Improving the quality of health care for chronic conditions. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2004;13(4):299-305.

- WHO. People-centred and integrated health services: an overview of the evidence. Interim report. Service Delivery and Safety, WHO, 2015.

- WHO. WHO global strategy on integrated people-centred health services 2016-2026. Executive Summary. Placing people and communities at the centre of health services, 2015.